The Istrian peninsular at the top end of the Adriatic Sea is a small enough spit of land in the European scheme of things but it has long been jam-packed with demographic tension. During the Late Medieval to Early Modern periods (1400s and 1500s) it could well have been one of the most contested areas on the planet. For a start, Istria was (and is) populated by three different ethnicities ― Italian, Slovenian, Croatian. In addition, this fractious littoral region was surrounded by three acquisitive empires ― Maritime Venice, Austrian Hapsburgs, Ottoman Turks.

An intriguing insight into this cockpit of animosity is given by its one element held in common, the Roman Catholic Church. In what is likely to have been an insular peasant society, serially suspicious and distrustful of any and all political authority, there was a shared space. Rare examples of seeing the world as if through one lens are still to be found in two tiny stone churches.

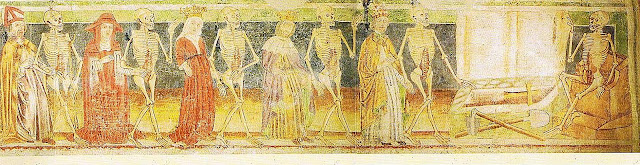

Tucked away in a forest on the site of an old monastic community near the village of Hrastovlje in Slovenia is the Church of the Holy Trinity. Hidden behind a thick stone wall on a hill near Beram in Croatia is the Sanctuary of St Mary of the Rocks. Between them these ancient buildings contain a priceless array of religious frescoes and wall-paintings, including a couple of striking Danse Macabre. The artists were local and their work unique to the region, despite responding to a number of outside influences.

The oldest fresco, at the church of St Mary at Skriline near Beram in central Istria, was completed in 1474. An inscription in Latin on the south wall translates:

In the honour of our Lord Jesus Christ, Amen, and the glorious Virgin Mother Mary and in the name of all Saints, this work was ordered by the community of Beram to be painted at the expense of the fraternity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This work was painted by Master Vincent of Kastav and finished in the month of November, the eighth day after [the feast of St] Martin, in the year 1474.

The more recent fresco at the church of the Holy Trinity near Hrastovlje was completed in 1490, a decade after the building's consecration by the bishop of Picenthis . On the north wall, "a barely visible text contains the name of the patron, Tomic Vrhovic ...: the date 1490; and an inscription indicating the name of the painter, 'Johannes de Kastva pinxit'."

A distinctive feature of both works is that the Dance Macabre runs from left to right, i.e. in the opposite direction to the Dances of Death in Holy Innocents in Paris, Old St Paul's in London, Dominican Convent in Basel, or the Notke Totentanz in Lubeck and Reval. A further point of difference is the limited cast of living dancers (10 at Hrastovlje, 11 at Beram) and the complete absence of explanatory text. In other words, each frieze is comparatively short in length and relies on graphics alone to tell the story. A reasonable interpretation is that these Istrian examples of the genre were directed at an illiterate audience.

At St Mary on the Rocks the chain of alternating living and dead characters is met by Death playing the bagpipes. It begins on the far right with a dead dancer leading the Pope:

"The pontiff is shown holding a money pouch in his hands, perhaps in an attempt to redeem himself, an interesting instance of anti-papal satire. The next living character behind him is the Cardinal, and then the Bishop, followed by the King wielding a sceptre topped with fleur-de-lys, and then the Queen who holds money in her hands. The next characters are the Landlord (whose profession of inn-keeper is indicated by a small barrel), the naked Child, the lame Beggar wearing a pilgrim's hat, the Knight in armour, and finally the Merchant who is standing beside a counter with [more!] money."

Inside this mural then, "a singular emphasis is placed on money". The Beram Danse Macabre shows a range of privileged classes discovering the uselessness of their wealth when trying to bargain with Death. In contrast, the dead dancers are celebrating, with "half the cadavers are playing instruments: trumpets, horns and lutes". From the early Middle Ages the Church often associated pipes and other wind instruments, along with drums, with the devil and demons: "Bagpipes were considered to be especially negative [i.e. non-sacred] instruments since they were typically played at peasant dances, which were condemned for their supposed unruliness and lasciviousness." A key feature (actually the lack of one) of the Beram Dance of Death is that there is no living figure who represents the peasants.

At Holy Trinity Church, the procession moves "towards an empty grave with a cross above it. Beside it sits Death, a hoe and a shovel lying crossed before him. Heading the procession is the first death dancer, holding the Pope (recognisable by his tiara) by the left hand ... the King and the Queen directly follow the Pope, each with their own skeletal companion. Behind them comes the Cardinal in a red chasuble and hat, followed by the Bishop and the Franciscan with a book under his right hand. Next is the Doctor who reaches into his bag in order to bribe Death with money from his purse, while the Townsman behind him leads the procession."

"The procession consists of eleven representations of the living: the pope, a king, a queen, a cardinal, a bishop, a monk, a physician, a merchant, a nobleman, a beggar, and a child stepping out of a cradle. The hierarchical order is much clearer than in Beram [but], again, there are no peasants. In fact the only representative of the lower classes is the Beggar." It is important to note that "a representation of the most numerous social class of the time ― the peasants ― is missing". There are no peasants in either mural.

"The Danse Macabre in Hrastovlje, just like the one in Beram, is not here as a momento mori for the local peasants ― they don't need to be reminded of their own mortality. It is here to criticize the ruling classes who try to buy more time, who try to bribe death, who flaunt their worldly riches at death's door ... It goes beyond reminding the viewer that we will all die one day: it emphasizes that members of the ruling classes will die too, that their position in the mortal world won't save them ... that death will mock their attempts and then take them.

As such, Danse Macabre is not a representation of the ubiquity of death. It is an image ― vivid, colorful, folkloric ― painted on the walls of two small village churches by local artists offering consolation [or vindication!], mocking the powers that be, and righting social justice. It is worth remembering that medieval people knew how to read a wall. These messages are not subtle ... the masters Vincent and Ivan of Kastav succeeded in creating a unique visual language and conveying a consistent, plain message, suitable for their public."

............................................................................................

The main reference for this post is

Tomislav Vignjevic, 2015, 'The Istrian Dance Macabre: Beram and Hrastovlje', in Mixed Metaphors: The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, <books.google.com>

The reference for the concluding paragraph is

Jeleno Dunato, 2021, 'Dance Macabre: Equality in Death in Medieval Istrian Frescoes', <psychopomp.com/deadlands/issue-04/danse-macabre>

Comments

Post a Comment