The Order's Second Commandery at Acre

"Acre was a hugely important city during the Crusades as a maritime foothold on the Mediterranean coast of the southern Levant and was the site of several battles, including the 1189-1191 Siege of Acre and the 1291 Siege of Acre. It was the last stronghold of the Crusaders in the Holy Land prior to that final battle in 1291. At the end of Crusader rule, the city was destroyed by the Mamluks ..."

"During the Crusades it was officially known as Sainct-Jehan-d'Acre ... after the Knights Hospitaller who had their headquarters there and whose patron saint was John the Baptist ..."

THE HOSPITALLER CITADEL AT SAINT-JEAN-D'ACRE

"From the first years of the Crusaders in the city, the Hospitallers received donated properties. In 1110, King Baldwin granted the Knights Hospitaller permission to keep the constructions located north of the Saints-Croix church. In 1130, these buildings were damaged during works near the church and the Hospitallers decided to move near the 12th century north wall of the city. This is the actual place of the commandery. In 1149, the first testimony of the commandery is in a document concerning the construction of the Saint-Jean church. In 1169, a pilgrim described the commandery of the Hospitallers of Acre as a very impressive fortified building.

"In 1191, during the Third Crusade, the Franks reconquered Acre after its siege. The Hospitallers moved back into their buildings. Jerusalem was no longer in the hands of the crusaders and so the commandery became the new headquarters of the order. A new construction campaign took place between the end of the 12th century and the 13th century, with new wings and additional floors.

"The current building which constitutes the citadel of Acre is an Ottoman fortification built on the foundation of the citadel of the Knights Hospitaller. Under the citadel and prison of Acre, archaeological excavations revealed a complex of halls which were built and used by the Knights. This complex was part of the Hospitallers' citadel, which was included in [i.e. part of] the northern defences of Acre. It contains six semi-joined halls, one recently excavated large hall, a dungeon, a refectory (dining room), and the remains of a Gothic church.

"The inner courtyard ... has an area of 1200 m² and is surrounded by a series of arcades ... The north wing was built along the north wall. There are vaulted rooms, 10 metres high, built during the Frankish era. The exterior wall is massive with a thickness of 3.5 metres ... The main hall of the south wing is housing the refectory ...

...........................................................................................................

THE MEDITERRANEAN MERCHANT FLEET

"Maritime transportation was vital for the operation of the Order, since it ensured the eastward flow of reinforcements and supplies, as well as communication between its houses across the Mediterranean."

[D Jacoby, 2016, 'Hospitaller ships and transportation across the Mediterranean', Ch 6 in The Hospitallers, the Mediterranean and Europe, 57-72.]

In 1178 "the Hospitallers obtained from Bertrand of Marseilles and his nephews William le Grose and Raymond Barral, joint viscounts of Marseilles, tax exemption for the transit, sale or purchase of their vessels and marketable goods in the harbour adjoining the sector of the city and other territories under their rule."

In 1197 "widow Empress Constance granted the Hospitallers in the Kingdom of Sicily the right to export goods to support the Convent in the Holy Land without paying taxes. In addition they were allowed to carry peregrini on their ships without having to transfer a portion of the fare collected from them to the royal court. The term peregrini covered both pilgrims and crusaders [the latter occasionally called milites peregrini or peregrini crucesignati]."

In 1210 "King Hugh I of Cyprus granted tax exemption throughout the island for the Order's trade in its own goods, the purchase of commodities for its own needs, and free anchorage in Cypriot ports for its ships carrying them."

In 1216 Hugh I of Baux and his wife Baralle granted the Hospitallers the right to build or anchor in the part and territory of Marseilles any type or number of ships that would sail to the Frankish Levant, Spain, or any other region to defend Christendom. The transport of their own goods, pilgrims, crusaders, merchants, and the latter's money on these ships, whether for fare and freight or without payment, was to be exempt [the concession included 'transit of timber assigned for shipbuilding']."

"The evidence surveyed so far ... The Hospitallers already owned one or several transport ships crossing the Mediterranean around mid-twelfth century. However the Order also relied on private carriers or chartered whole ships. The loss of numerous estates in the Levant in 1187 substantially reduced its self-supply and revenues ... despite the temporary recovery of some lands until the mid-thirteenth century. As a result, the Hospitallers in the Levant were compelled to rely ... on supplies from the West ... The frequent transfer of reinforcements, and especially of supplies, across the Mediterranean after 1191 induced the Hospitallers to purchase ships or commission their construction on a much larger scale than before ..."

Attested voyages of Hospitaller-owned ships Marseilles ⇆ Acre

Falcon 1238 1248 Angel 1270

Countess 1246 1248 Bonaventura 1278

Griffon 1248 St Andrew 1279

All these vessels were naves, round hulled sailing ships, built in Marseilles, their home port.

It was on these very special ships, the Trade Nava and the Crusades Nava, that the Crusaders landed in the Holy Land. Their origin in the Byzantine cargo ship style is revealed by their working prow (vessels being run up onto the sand to load and unload), the galley type rear with external steering oar, the tilted front mast, and the rigging for lateen sails. The Mediterranean Nave most commonly had two masts fitted with a mixture of sails, both square and lateen. The nave above right (nef croisades) shows the arms of Richard the Lionheart, a wealthy king as well as Crusader, indicating a specially commissioned ship. In general, the knights and common pilgrims who left for the later Crusades took a route across France or Italy, boarded at Marseilles or Messina for Malta or Crete, and then onto Palestine. Local vessels like the nave above left (nef marchande) were used.

"In 1288 the Hospitallers in Acre equipped a saitie, an elongated, oared vessel capable of swift sailing, yet no galleys of the Order are attested until 1291. This distinguishes the Hospitaller fleet before that year from the one operating later from Cyprus, which included a naval force of galleys."

In other words, the Hospitaller fleet in the 12th and 13th centuries was restricted to merchant vessels only. Even then, and "despite increasing investment in deep sea going ships after 1191", the Knights had an opportunistic shipping policy. They "took advantage of private ships engaged in commercial sailings, hired whole vessels, purchased them, or commissioned their construction." The Order was "never capable of ensuring, on its own, the volume of maritime transportation that it needed."

..............................................................................................

THE MAGNIFICENT FORTRESS OF MARGAT

"In the face of such a united Moslem campaign as that of 1187 by Saladin, which reduced the kingdom of Jerusalem to a coastal fragment with a few inland strong points only in Christian hands, it was all the Franks could do, after defeat in battle, to keep a few of their castles ... Krak des Chevaliers and Margat, both Hospitaller castles, held out inland."

[RA Brown ed. (C Coulson, M Bennet etc.), 1980, Castles: A History and Guide, Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset].

1. Margat

Location: Qalaat Marquab, 4km above the town of Baniyas, on the coast of Syria.

Description: Fortified triangular area, with sides measuring 1300 feet in length and a strong inner bailey, including a huge circular tower.

History: An Arab fortress in the 11th century, Margat came into Crusader hands in 1118. Unable to afford repairs after serious earthquakes, its lord sold the castle to the Hospitallers in 1186. The Order began an extensive rebuilding programme, constructing an inner bailey behind a wide ditch. This included vaulted halls, a fine chapel, and a circular donjon.. This two-storey tower, 100 feet in diameter, was central to the defensive system and when it was undermined during the Mamaluke siege of 1285, the knights were force to surrender.

Merkab, Marquab, Chateaux de Margat

[Richard Pococke, 1745, A Description of the East and Some Other Countries. The account of an English traveller to the Middle East in the eighteenth century.]

"They told me that the governors of these countries took up their residence at the castle of Merkab, to which we went by a steep ascent of an hour and a half. The castle is about half a mile in circumference, taking the whole summit of this mountain; it is of a triangular figure, and exceedingly strong, the inner walls are fifteen thick, and there is another wall on the outside which encompasses it almost all around; for in one part, where its natural situation is very strong, there is only a single wall. Under the buildings there are great vaults, or cisterns, cut out of the rock to preserve the rain water, and out of these that the black stone was hewn, with which the greatest part of the castle is built. The church which is towards the east end of the castle is well built, mostly of a black stone; it is adorned with semicircular pilasters, which are tolerably well executed; ( ... ) Adjoining to the church on the east are some large rooms. At the east and west end there are two very large round towers, each one of which encompasses a small court. They have a tradition, that this castle was a work of the Franks, and it was certainly held by the knights of Jerusalem. The governor said to us, 'This fabric was raised by your fathers, and we took it by the sword'."

HIERARCHY AND COMMUNAL LIFE IN THE CASTLE

"By the beginning of the 13th century Margat had become the most important administrative centre of the Hospitallery in Syria and one of the largest fortified Crusader sites ... there were more than a thousand armed men employed for service, even during peacetime ... As was the case with other castle garrisons of the military orders, only a small part of the garrison belonged to ... the Hospitaller elite. However due to its prominent position amongst the Hospitaller hierarchy there are likely to have been a relatively high number of full members of the Order serving here ...

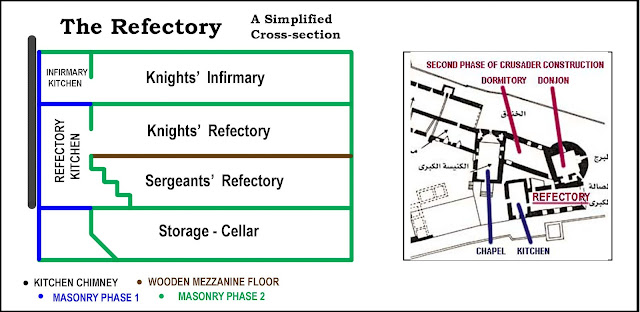

The Refectory. Given the presumably large size of the contingent of Hospitaller knights stationed at Margat and their monastic lifestyle, requiring a communal life that included shared meals, a hall of suitable size had to be located in the central part of the castle ... this refectory hall has been identified as the great barrel vaulted hall situated in the western edge of the Hospitaller Margat. Being close to the chapter house, dormitory and the chapel, the refectory hall was bordered in the north by a kitchen building with a chimney, where a central cooking area comprising of four ovens was excavated, and which had a southern doorway opening into the refectory."

[Shillito et al, 2014, 'Micromorphological and geochemical investigation of formation processes in the refectory at the castle of Margat (Qal'at al-Marqab), Syria', Journal of Archaeological Science, 50, 4151-459.]

"... the construction of a large rectangular building ... the refectory complex ...

The large ground-floor, measuring 22.5 X 9 metres and lit by only one slit-window, was a storeroom for the refectory and, given its unique and almost metre-wide ventilation shafts, must have served as the main cellar from which wine barrels were brought up to the refectory ... The hall above, measuring 25.5 metres, was the main dining area of the citadel and was lit from the west by a double row of windows. This, combined with the series of corbels in the eastern and western sidewalls and the fact that the kitchen door opens halfway up the northern wall of the hall, makes it evident that the refectory was divided [horizontally] by a wooden mezzanine floor. The upper [part of the] hall, with its own stepped entrance from the neighbouring courtyard, might have served as the knight's refectory, and the lower one with its doorway also on the eastern side of the hall, as the dining hall of the sergeant brothers ... the top of [the refectory wing] remained unbuilt at this time and had only a crenellated parapet.

... Sometime after 1202 the building also had a new construction placed on its roof ... this new hall had a neighbouring area at its northern end, which shared the same chimney with the kitchen [below] and so it is tempting to see it as another lesser kitchen. As the statutes [of the Order] recommended having a separate 'table' for the knights infirmary, the lightly constructed building could itself have been the knights' [own] infirmary, and would have been in close proximity to their dormitory."

[B Major, 2019, 'Constructing a Medieval Fortification in Syria: Margat between 1187 and 1285', in Bridge of Civilizations: The Near East and Europe c. 1100-1300, Archaeopress Publishing, Oxford, Ch 1, pp 1-23.]

........................................................................................................................

MAINTAINING THE PRIVILEGES OF THE SICK

It is sometimes too easy to forget that the primary mission of the Order was to minister to the sick. That they were absolutely sincere in this for most of the first century of their existence is reflected in the RULE OF THE BLESSED RAYMOND DU PUY (1120-1160). Their individual commitment is contained in clause 1 that stipulates the monastic promises of Chastity, Obedience and Poverty. Their joint commitment is related in clause 16:

"HOW OUR LORDS THE SICK SHOULD BE RECEIVED AND SERVED.―

... when the sick man shall come there, let him be received thus, let him partake of the Holy Sacrament, first having confessed his sins to the priest, and afterwards let him be carried to bed, and there as if he were a Lord, each day before the brethren go to eat, let him be refreshed with food charitably according to the ability of the House."

The particulars of their service, and the extensive international network of supporting 'Hospitals' they depended upon to sustain their work, is contained in the STATUTES OF FR. ROGER DES MOULINS (1177-1187) from the Chapter-General of 1181. A general statement of normal or expected behaviour by the brethren is made under the heading:

"CONFIRMATION BY THE MASTER ROGER OF THE THINGS THAT THE HOUSE SHOULD DO:

1.Firstly, the Holy House of the Hospital is accustomed to receive sick men and women, and is accustomed to keep doctors who have the care of the sick, and who make the syrups for the sick, and who provide the things that are necessary for the sick ...

10. These [additional items specified in paragraphs 2. to 9.] are the special charities decreed in the Hospital, apart from the Brethren-at-Arms whom the House should maintain honourably [italics added], and many other charities there are which cannot be set out in detail each one by itself."

It is clear that the first function of the "Holy House of the Hospital" was to receive the sick, a priority that comes before maintenance of "the Brethren-at-Arms". The second clause of the statutes affirms this emphasis on healthcare ― "... it is decreed with the assent of the brethren that for the sick in the Hospital of Jerusalem there should be engaged four wise doctors, who are qualified to examine urine, and to diagnose different diseases, and are able to administer appropriate medicines".

There was a pattern of medical inter-connectivity established between the different commanderies, or priories, with the eighth clause stating what contributions each branch was to make to the central effort: "The Prior of Mount Pelerin (i.e. Tripolis) should send to Jerusalem two quintals [2 cwt.] of sugar for the syrups and medicines and the electuaries [a composition of medicinal powders mixed with honey or sugar syrup] of the sick. For this same service the Bailiff [commander] of Tabarie (i.e. Tiberius) should send there the same quantity."

This high degree of cooperation among the separate elements of the organisation is mirrored in the supply of textiles required in nursing the sick. The Hospital at Jerusalem had high standards:

"3. And thirdly, it is added that the beds of the sick should be made as long and as broad as is most convenient for repose, and that each bed should be covered in its own coverlet, and each bed should have its own special sheets.

4. After these needs is decreed the fourth command, that each of the sick should have a cloak of sheepskin, and boots for going to and coming from the latrines, and caps of wool ...

6. Afterwards it is decreed the sixth clause, that the biers of the dead should be concealed in the same manner as are the biers of the brethren, and should be covered with a red coverlet having a white cross ...

8. It was also decreed, when the council of the brethren [i.e. Chapter-General] was held, that the Prior of France should send each year to Jerusalem one hundred sheets of dyed cotton to replace the coverlets of the sick poor ...

In the self-same manner and reckoning the Prior of St Gilles [a port of embarkation for French pilgrims to the Holy Land] should purchase each year the like number of sheets of cotton and send them to Jerusalem ...

The Prior of Italy each year should send to Jerusalem for our lords the sick two thousand ells [3,000 yards] of fustions [thicker twilled cotton fabric] of divers colours ...

And the Prior of Pisa should send likewise the like number of fustions ..

And the Prior of Venice likewise ...

The Bailiff of Antioch should send to Jerusalem two thousand ells of cotton cloth for the coverlets of the sick ...

The Prior of Constantinople should send for the sick two hundred felts [wool and hair matted together ('woolen caps'?)] ..."

However, this unity in serving the needs of stranded, wounded, diseased and dying pilgrims, came to an abrupt halt when Saladin ejected the Christians from Jerusalem. There was no Hospital, or any geographical centre for that matter, to send donations to. Following a five year war against triumphant Islamic armies, and at its end, the Hospitallers were as much a military order as the Templars. "The gaps in their ranks had been filled by a constant stream of young Knights from Europe, to whom the strict conventual discipline and the ancient charitable traditions of the Order were quite unknown". And "during the weak rule of Master Geoffrey de Donjon (1193-1202) all discipline seems to have disappeared". The challenge facing the newly elected outsider candidate Alfonso of Portugal was steep.

During the short period that Alfonso was Master of the Hospitallers (1202-1206) he "devoted his entire energies to the restoration of the old conventual discipline". He convened a Chapter-General at Margat Castle. The STATUTES OF FR. ALFONSO OF PORTUGAL are commonly known as the STATUTES OF MARGAT and remained the standard constitution of the Order for the next sixty years. The heart of his achievement is summarised in the first section. It states:

"And it was said that the customs of the church [the Convent, the House, the Hospital] should be maintained, just as it is written above ['when they were known, by the witness of ancient and wise brethren, to have existed of old time'], that the privilege of the sick should should be maintained, that is to say concerning cloaks, boats, caps, the maintenance of [abandoned] children, the pittance [allowance] of wine when the brethren shall have it at double festivals, that they should be maintained just as it is written."

Archaeological evidence of the Order re-establishing a Hospital as central to their calling remains unexcavated beneath the Citadel at Old Acre. However their commitment to caring for the sick is obliquely confirmed by the existence of the Sugar Bowl Hall, a work area situated close to where the Hospital is believed to have been, on the northwestern side of the fortress. As the Statutes of Roger de Moulins showed, there was a strong connection between sugar and the preparation of medicines at the Jerusalem Hospital during the previous century.

"Sugar Bowl Hall:

This is a three-story building. The lower floor houses a large water reservoir that collects rainwater. The reservoir is divided into two interconnected halls by means of a large aperture. Each of the halls is 13 X 5 square metres and 7.5 metres tall, and has a barrel vault ceiling. The sugar bowl hall is built above the reservoir. This hall as well is divided into two spaces that match the reservoir halls. The hall is 7 metres tall and has a barrel vault ceiling, parts of which have collapsed. When the hall was excavated, hundreds of earthenware pottery pieces arranged in rows were discovered on the building's floor. These pottery pieces are 'sugar utensils', namely cone-shaped [vessels] made of pottery with a drainage hole on the bottom. The tools were stacked in rows along the eastern wall of the hall. Straw was placed on the floor in between the rows of utensils in order to prevent breakage. Dozens of small jars called 'molasses jars' were found on the floor in another section of the hall. These utensils are used at the end of the process [of] crystalline sugar production ... This large storage room, which contained a great many sugar production utensils, reinforces the documented evidence we have found whereby the Hospitallers were among the leading developers of the sugar industry in the [Acre] region ..."

[The main reference for this section has been Rule, Statutes and Customs of the Hospitallers, 1099-1310, translated by EJ King (1935, Methuen, London). The final quotation is from <akko.org.il/attraction/the-knights-halls>.]

.............................................................................................................

Comments

Post a Comment