The Tallinn Fragment

1. REMEMBER AT ALL TIMES TO BRING GOOD DEEDS WITH YOU

"I call all and everyone to this dance:

pope, emperor, and all creatures poor, rich, big , or small.

Step forward, mourning won't help now!

Remember though at all times to bring good deeds with you

and to repent your sins

for you must dance to my pipe."

Totentanz of Reval (Tallinn)

"On 23 August 1468 Lubeck's city council issued a letter to its counterpart in Reval requesting the transfer of the properties of a Reval cleric, Diderik Notken, to Bernt Notke, painter and burgher of Lubeck. According to this letter, Diderik had bequeathed all his real property in Reval for the wellbeing of his soul and for his relatives (to slichied ziner zelen vnde behuff syner angeborenen vrund). The painter referenced in this letter was the same Bernt Notke (c. 1440-1508) who around 1463 painted a cycle called the Dance of Death (Totentanz) in the chapel of St Matthew in Lubeck, which he later replicated under the belfry of St Nicholas Church in Reval. In the absence of other documentation of its commission, this letter has been used as evidence that Diderik Notken's donation for his soul was spent on the production of the Reval Totentanz. It is undoubtedly the most famous surviving medieval artwork in the Baltics."

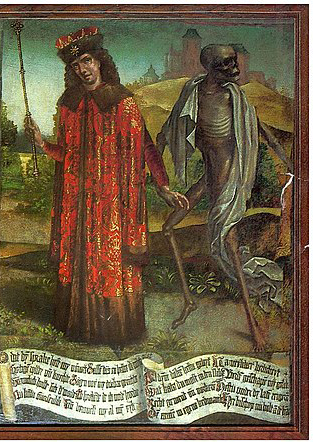

"Dance Macabre was a frequently occurring motif in medieval art. The fragment of Reval's Totentanz reflects the main characteristics of the genre. It depicts Death, playing bagpipes, a preacher in a pulpit who alerts the audience, and several figures ― a pope, a cardinal, and emperor, an empress, and a king ― who are led into the dance by cadavers. The other fragments of the Reval Totentanz have been lost. The Lubeck Totentanz painted by Bernt Notke contains more characters: twenty-four pairs of the living and the dead from all social classes, both secular and religious, including townspeople such as a burgomaster, a craftsman, and a merchant. Both works have a familiar urban landscape as their background; the backdrop to the Lubeck Totentanz is recognisably the city, while in Reval the background is a more stereotypical Hanseatic scene. Along with the life-sized and life-like figures, the background served to reinforce a 'sense of actuality' for viewers."

"Both works were created during or directly after a plague that had visited both cities; it broke out in Lubeck in 1463/64 and reached Ravel in 1464/65. The Reval Totentanz was placed in the public space ― in the parish church ― near the place where the dead were buried. In the Totentanz the images interplayed with the text written under the figures to convey a clear message: memento mori, death is inevitable. Most members of the urban elite belonged to the parish of St Nicholas, where the altars of the elite guilds and brotherhoods were located. The Totentanz reminded them to care for the afterlife and about their commemoration. In the Totentanz, Death directly addresses both the painted figures and the parishioners of St Nicholas: '[...] you must follow me and become what I am'. The message of Reval's Totentanz was directed towards the elite, to remind it of the temporary nature of its own power and wealth. And so members of the late medieval urban elite were well aware of that, and they used their power and wealth to ensure the well-being of their souls through institutions, by making extensive provisions for memoria, both individually and collectively."

"Merchant elites, including their family members, accounted for between a tenth and a fifth of the urban population in the late medieval Hanseatic cities. In late medieval Riga and Reval [the German name for Tallinn], with approximately 6000-8000 and 5000-6000 inhabitants respectively, the merchant elites numbered several hundred individuals. The elite in Riga was comprised of around 100-120 long-distance merchants who belonged to the Great Guild as well as their family members. They lived alongside a group of approximately 100 apprentices and foreign [i.e. non-German origin] merchants. In late fifteenth century Reval, around 540 townspeople belonged to the elite long-distance merchant families [i.e. of German origin], which were represented in the merchant guild and other elite brotherhoods.

Since the late-thirteenth century, merchants controlled the urban government of all Hanseatic cities and excluded artisans from power. In Riga and Reval, the city councils were controlled by the exclusive merchant Great Guilds, and only their members were allowed to join the council. Membership of the Great Guild was usually combined with activities in the charitable Table Guild ['Remember at all times to bring good deeds with you ...']; before proceeding to the Great Guild, young merchants in Riga and Reval usually belonged to the brotherhood of Black Heads [associations for young unmarried or foreign merchants that excluded artisans, priests, and indigenous non-Germans].

In Riga and Reval, collective memoria was 'a constitutive element' that formed the merchant guilds as social groups ... The first statutes of the Rigan kumpanie, issued in 1354, decreed that on the day after the drunke (drinking feast), the guild's brethren in remembrance of all the guild's dead had to spread a pall (coffin cover) in the church, light four candles, and then sing a vigil; five memorial masses followed on the next morning. In Reval the statutes ordained that memorial services ― a vigil and three memorial masses sung the next morning ― were to be performed at the death of every brother in the presence of a pall and lights ...The Great Guilds also took responsibility for memoria of their impoverished members by granting them funerals with a pall and lights ...

The statutes of the Reval Great Guild stated that the guild had to pay one ferding to the priests of St Nicholas church on Shrovetide for monthly remembrance. In St Nicholas church, the guild had two altars, dedicated to St Blaise and St Christopher, at which the priests celebrated the memorial services."

[Note that all the above text in italics is quoted from Ch 5: 'Memoria and Urban Elites', by Gustavs Strenga, in Remembering the Dead: Collective Memory and Commemoration in Late Medieval Livonia, pp 151,153-154, 157-158, released by Brepols Publishers in 2023].

<brepolsonline.net/doi/epdf/10.1484/>

2. LUBECK MASTERS HERMAN RODE AND BERNT NOTKE AT REVAL

"... the Niguliste (St Nicholas) Church was founded in 1230 by and for German merchants who made their way to Reval through Gotland ... Intended for the performance of both religious and secular ceremonies, it was also used as a fortress and had storerooms upstairs ... sometime around 1370, St Mathews Chapel, later renamed in honor of St Anthony, was erected against the south wall of the church, next to the tower, and was enlarged between 1486 and 1493. St Matthew's Chapel apparently served as a funerary chapel: tombstones dating from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century still cover the floor. It was for this chapel that the Lubeck master Bernt Notke was commissioned to paint the Dance of Death ...

Reval ... had close connections with the city of Lubeck ... These times can be seen ... in the active import of works of art into Reval, especially during the fifteenth century. Between 1478 and 1482, for example, Herman Rode and his assistants, all hailing from Lubeck, executed a high altar for the Niguliste Church ... Bernt Notke, as a Lubeck sculptor and painter, had [also] established wide-ranging connections with Scandinavian and Baltic communities ... In 1483 he completed an altarpiece commissioned by the Reval town hall for the Puhavaimu Kirik ('Church of the Holy Spirit'), and around the same time he executed the painting of the Dance of Death for St Matthew's (St Anthony's) Chapel in the Niguliste Church."

[Elina Gertsman, 2003, 'The Dance of Death in Reval (Tallinn): The Preacher and his Audience', Gesta 42.2, p 144]

3. TRANSLATION OF ORIGINAL VERSES IN MIDDLE LOW GERMAN

The surviving fragment of the Tallinn Dance of Death makes it very clear that text and image were to be taken together. By placing the script so legibly and directly beneath the character whose speech it represented, the viewer was prompted to use the writing to interpret the picture, and the picture to make sense of the writing. The artist makes obvious his desire for both elements to be consumed interactively. This purpose is reinforced by the text being presented in Middle Lower German, the common language (or lingua franca) of the Hanseatic League from at least the thirteenth century through to its demise in the seventeenth. Bernt Notke's audience was the merchant class, the most important parishioners of St Nicholas, and the sponsors of two of its altars. As leading commercial citizens, they were educated as well as religious ― numerate and literate.

O, reasonable creature, whether poor or rich! I call all and everyone to this dance:

Look here into this mirror, young and old, pope, emperor, and all creatures

and remember all poor, rich, big, or small.

that no one can stay here Step forward, mourning won't help now!

when death comes as you see here. Remember though at all times

If we do good deeds to bring good deeds with you

we can be together with God. and to repent your sins

We will get the reward we justly deserve. for you must dance to my pipe.

My dear children, I want to advise you

not to lead your sheep astray,

but to be to them a good model

before death suddenly appears at your side.

Pope, now you are the highest, O Lord God, of what use is it to me―

let us lead the dance, me and you! even though I reached a high position

Even though you may have been God's I must here and now

representative, become a handful of earth just like you.

a father on earth, received honor and glory Neither esteem nor wealth can be of any

from all the men in this world, you must use to me

follow me and become what I am. for I have to leave it all behind.

What you loosed was loosed, what you bound Let this be an example to you, you who will

was bound, be pope

but now you lose your great esteem. after me as I was in my time.

Death to the Pope

[ ... ] (indecipherable)

Emperor, we have to dance!

O death, you ugly figure, You were chosen, ―ponder it well!―

you completely change my nature. to protect and guard

I was rich and powerful, the holy church of Christendom

the most powerful one without compare. with the sword of justice.

Kings, dukes and noblemen But haughtiness has blinded you,

had to bow before me and honor me. you didn't know yourself.

Now you come, horrible apparition, My coming you did not expect.

to make worm feed of me. Turn you to me now, empress.

Empress Death to the Empress

I know it's me death means. Utterly insolent empress,

I've never been so terrified before. it seems to me that you have forgotten me.

I thought he was not in his right mind, Come here! It's time now.

for I am so young and an empress too! You believed I would spare you?

I believed I had great power, Not at all, however great you may be, but of death I never thought you have to follow me to this roundelay

or that someone else would hurt me. and all you others as well!

Oh, let me live a little longer, I pray you! Stop, follow me, cardinal.

Have mercy on me Lord, not that it has to You were esteemed

happen! Like an apostle of God on earth,

There is no way for me to escape from you. that you may support the Christian faith

Whether I look before or behind with words and other virtuous deeds.

I always sense death close to me. But in your great haughtiness

Of what use can the high rank be to me you sat on your high horse.

which I attained? I have to leave it behind Therefore now you have to worry even more!

and instantly become less worthy Step forward now, noble king!

than a foul stinking dog.

Oh death, your words have scared me! All your thoughts were about

This dance I haven't learned. worldly splendour.

Dukes, knights, and squires How does that help you now? You have to sink

served me precious dishes into the earth

and every one took heed and become like me.

not to speak the words I disliked to hear. You let bent and perverted laws

Now you come unexpectedly prevail during your kingship,

and rob me of my entire kingdom! you wrought violence on the poor as if they

were slaves.

Bishop, give me your hand.

[Elina Gertsman, 2003, Appendix: Text and Translation of the Reval Dance of Death, 'The Dance of Death in Reval (Tallinn): The Preacher and his Audience', Gest, 42.2, 143-159.]

Comments

Post a Comment