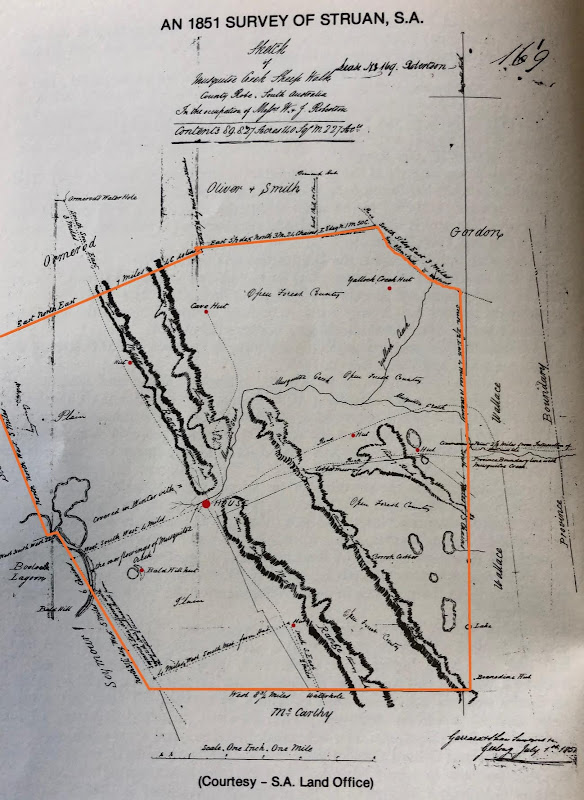

Sketch of Musquitoe Creek Sheep Walk - 1851

The squatters John and William Robertson entered the "New Country" and settled on "Robertsons Plains" in 1842. In the era of Occupation Licences they held No. 64, claiming 60 square miles of land (38,400 acres). When the system changed to Pastoral Leases in 1851, they held No. 169 and claimed 140 square miles (89,800 acres). The story of their decade of expansion and consolidation is illustrated by a contemporary survey of the "Struan Run".

Held by the South Australian Lands Office, and drafted by Garrald & Shaw, surveyors from Geelong in July 1851, the map has the long but descriptive title of

Sketch of Musquitoe Creek Sheep Walk,

County Robe, South Australia

In the occupation of Messrs W & J Robertson

Contents 89,827 Acres, 140 Sq M 227 Acs.

and is annotated "Lease No. 169, Robertson". The relatively detailed "Sketch" makes clearer what is only hinted at in the general licence and lease maps posted in the previous article on John Robertson of Struan House.

(from Max Neale, 1984, Redgums and Hard Yacca: A History of Elderslie and Langkoop 1843, Mount Gambier SA, p 20)

The 'sheep walk' is an amalgam of two distinct agricultural zones. It is separated into two almost equal halves by the Naracoorte and Caves Ranges (Stringy Bark and grey sand country) running northwest-southeast. To the west of these natural geographical lines the land is described as "Plain". To the east it is nominated "Open Forest Country".

Significantly, the operational centre of the station, the homestead, is situated where the Mosquito Creek breaks through the low sand ridges. This is the site that is not only an approximate mid-point from all boundaries. It is also where one type of country becomes another type of country.

It is not necessarily a flight of literary fancy to imagine the bothers emerging from the ranges and experiencing a moment of revelation, of 'recognition'. Behind them were the gentle undulations of the benign Red Gum country they had traversed to reach this point. Before them stretched bleak and treeless plains, a land all too clearly inundated during the wet winter months. As the Sketch depicts it, the plain banks of the meandering creek they had been following now dispersed into a fan of smaller tributaries -- from here on, the "Plain" is said to be "Covered in Winter with the overflowing of Musquitoe Creek".

From a pastoralist's perspective, the two types of country complement each other. Red Gum country is 'early country'. Grass responds quickly with growth in the 'spring flush' and is less prone to toxic bogging in winter. But it also 'finishes' quickly and it is difficult to continue with livestock without reducing numbers or supplementary feeding. The heavy black soils of the Mosquito Plains are water-logged in winter (even more so before the drainage schemes in the South East). The plains also retain much of their spring growth through summer and autumn as 'dry feed'. Together the 'early' and 'late' types of country offer a balance to the grazier, an all year round 'bank of grass'.

Looking out over the windswept horizons of flat country in front of them, the brothers may have been reminded of the Highland moors of their upbringing in Badenoch (Gaelic: baideanach; 'drowned' or 'submerged' land).

REMEMBERING THE BARONY OF DUNACHTON

1. "Dunachton (Gaelic: dun, fort of, achton, Ecton, a Pictish king) lies on the north side of the River Spey...A small estate owned by the chief of the clan Mackintosh (Gaelic: mac, son of, toiseach, captain, chief, or principal man)."

[Alexander MacBain, 1890, 'Badenoch: Its history, clans and place names', Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, <www.electricscotland.com/history/articles/badenoch,htm>]

2. "...life in Dunachton was harsh. Moorland and hill constituted 95% of the estate, with both arable and pasture extremely limited. Badenoch's land locked mountains subjected it to some of the harshest climatic conditions in Britain, rendering harvests precarious. Survival thus depended largely on pastoral farming, particularly cattle -- by far the most important sector of the Badenoch economy."

[David Taylor, 2019, 'The Robertsons of Alvie in Van Diemens Land', History Scotland]

3. The eighteenth century Badenoch farm was a closely integrated eco-system, generally running in a narrow strip from river to distant mountain top. It was this 'vertical' alignment that provided the essentials of self-sufficiency; the riverside for hay meadows and winter pasture; the natural terraces and lower slopes for arable and grass; the woodlands for timber, bark and winter pasture; the [upper] moorland for [summer] grazing, peat, turf and heather; the higher mountains for sheilings [summer grazing]."

[David Taylor, 2015, 'A Society in Transition: Badenoch 1750-1800', PhD Thesis, University of Highlands and Islands (Edinburgh University), p 57]

An introduction to William and John Robertson's experience of Badenoch (born at Dunachton 1811 and 1808, left 1838) is provided in the following extract from a map of Scotland first published in 1750. It illustrates the traditional operation of a Highland estate under the clan system, (in this case "The Laird of McIntosh for Kincraig-Dunachton-Pittourie" as per Land Tax Rolls for Alvie Parish in 1691), with scatterings of fermtouns and runrig agriculture.

(William Roy, c.1750, Military Survey of Scotland, 'The Great Map', National Library of Scotland, <maps.nls.uk/roy>)

Macintosh of Macintosh, The Macintosh of Moy Hall, owned the land above the line of the River Spey and Loch Insh. It formed a mosaic of communities or fermtouns (red dots) and their associated infields (raised ridges of cultivation) and outfields (common pasture and woodland) -- including Dunachton, site of the old fort, Dunachtonmor (Big Dunachton), Dunachtonbeg (Little Dunachton), Clith, Kincraig, and Pitourie. Access to the all important upland moors and sheilings was by walking their cattle and horses up the Dunachton and Leault Burns leading to the top of this section of the map.

Hemming the arable area in are Creag Mhor and An Suidhe, the peaks at the edge of the mountain range known as the Monadhliaths. Up there, the acid parent rocks have eroded in part to form "broad rolling peat covered plateaus". While this remote region is covered in snow in winter, it becomes "heather moorland" in summer. These highly prized zones of exposed country were really what made existence in the fermtouns sustainable. Shelters (bothies) were built, cows were milked and 'followers' fattened, and peat fuel was cut and dried for carrying back down to the winter settlements.

(OC Lelong, 2002, 'Writing People into the Landscape: Approaches to the Archaeology of Badenoch and Strathnaver', PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow, pp 43-44)

Interesting to note on this bit of Roy's map is the incongruous symmetry of straight lines in the bottom left hand corner. Raiths was a small sign, an out of time experiment, of things to come. It was the work of another Macintosh. While "incarcerated in Edinburgh Castle after the 1715 Jacobite Rising, Brigadier Macintosh of Borlum, Laird of Raitts, produced his famous treatise on agricultural improvement...An Essay on Ways and Means for Inclosing, Fallowing, Planting etc." (Edinburgh, 1729). The result of his enthusiasm was this first evidence of enclosure in the district; essentially, the end of common grazing by the fencing out of livestock.

(Taylor 2015, p 130)

The eighteenth century was an age of agricultural 'improvement' in the Scottish Highlands, with 'progressive' clan chieftains evicting their tenants in estate clearances, and amalgamating the fermtouns and runrigs into small arable farms instead. Advocates of 'modern' farming practices often took a pompous tone, implying that everything to do with the old ways were only sentimental obstructions to increased productivity.

"Mackintosh himself had begun just such a process in 1791-92, with the issue of eviction notices to all his Dunachton tenants, a process not finally complete until the 1820s. By then the old runrig farms had been entirely replaced by nineteen small to medium independent farms resulting in the loss of many of the old tenantry." (a possible reduction of 66 families from an original 85 'long-houses' or turf huts marked on Roy's map in 1750).

(Taylor 2019)

It seems that the parents of John and William Robertson, John and Mary nee McBain, brought up their family of 10 children on one these 'new' farms. They died in Alvie Parish in 1843 and 1844 respectively. Their eldest son Angus and his family did not emigrate to the Australian colonies until 1852. These dates suggest some security of tenure on the 'family' farm, perhaps a longer fixed term lease, or a pattern of lease renewal.

In any event, most of John and Mary's immediate descendants did leave Badenoch between 1838 and 1852, and most went on make their initial foothold the small 'first Struan' established by John and William on the Wannon River in Victoria about 1840. By creating this 'beachhead' the two brothers encouraged and 'enabled' others in the family to follow. However there probably was a strong 'push-factor' to their exodus from Dunachton too.

The nineteen individual farms were intended to be an 'improvement' on the old style of co-operative subsistence. However 'independence' meant the former integrated system of cultivating the lower valley and grazing the upper moors was severed. Landlords like Macintosh of Macintosh took an 'efficiency premium' of renting out the non-arable parts of their estates to game shooters from the south or converted them into large 'sheep walks'. The tenants who farmed along the banks of the Spey lost access to the peat grounds and summer pasture.

The lesson learnt by the Robertson family may well have been that the larger, but still small (less than 50 acres), enclosed farms actually restricted productivity and opportunity.

When John and William emerged from the gap in the Naracoorte Range in 1842 and saw the vast expanse of treeless plains before them, they 'knew' what they were looking at. It was 'the other half' of the farm back at Dunachton.

Comments

Post a Comment