"No. 1"

DARKNESS AT NOON written by Arthur Koestler 1938-1940

Translated by Daphne Hardy and published by Macmillan 1941

<files.libcom.org/files-"Arthur-Koestler"-Darkness-at-Noon.pdf>

The cell door slammed behind Rubashov ...

An hour earlier, when the two officials of the People's Commissariat of the Interior were hammering on Rubashov's door in order to arrest him, Rubashov was just dreaming that he was being arrested ... Then the light blazed on and the mist parted ... He dried his forehead and the bald patch on the back of his head with the sheet, and blinked up with already returning irony at the colour-print of No. 1, leader of the Party, which hung over his bed on the wall of his room ― and on the walls of all the rooms next to, above, or under his; on all the walls of the house, of the town, and of the enormous country for which he had fought and suffered, and which now had taken him up again in its enormous protecting lap. He was now fully awake; but the hammering on his door went on.

The two men who had come to arrest Rubashov stood outside on the dark landing and consulted each other. The porter Vassilij, who had shown them the way upstairs, stood in the open lift doorway and panted with fear. He was a thin old man; above the torn collar of the military overcoat he had thrown over his nightshirt appeared a broad red scar which gave him a scrofulous look. It was the result of a neck wound received in the Civil War, throughout which he had fought in Rubashov's Partisan regiment. Later Rubashov had been ordered abroad and Vassilij had heard of him only occasionally, from the newspaper which his daughter read to him in the evenings. She had read to him the speeches which Rubashov made to the Congresses; they were long and difficult to understand, and Vassilij could never quite manage to find in them the tone of voice of the little bearded Partisan commander who had known such beautiful oaths that even the Holy Madonna of Kasan must have smiled at them. Usually Vassiliv fell asleep in the middle of these speeches, but always woke up when his daughter came to the final sentences and the applause, solemnly raising her voice. To every one of the ceremonial endings, "Long live the International! Long live the Revolution! Long live No. 1!", Vassilij added a heartfelt "Amen" under his breath, so that the daughter should not hear it; then took his jacket off, crossed himself secretly and with a bad conscience and went to bed. Above his bed also hung a portrait of No. 1, and next to it a photograph of Rubashov as Partisan commander. If that photograph were found, he would probably also be taken away.

DARKNESS AT NOON continued

At seven o'clock in the morning ― two hours after he had been brought to cell 404 ― Rubashov was woken by a bugle call ... It was not yet quite day; the contours of the can and of the wash-basin were softened by the dim light ...

So I shall be shot, thought Rubashov ...

"So they are going to shoot you", he told himself ...

"The old guard is dead", he said to himself.

"We are the last". "We are going to be destroyed" ...

"The old guard is dead", he repeated and tried to remember their faces.

He could only recall a few.

Of the first Chairman of the International, who had been executed as a traitor, he could only conjure up a piece of a check waistcoat over the slightly rotund belly. He had never worn braces, always leather belts. The second Prime Minister of the Revolutionary State, also executed, had bitten his nails in moments of danger. ''...History will rehabilitate you, thought Rubashov, without particular conviction. What does history know of nail-biting?

He smoked and thought of the dead, and of the humiliation which preceded their death. Nevertheless, he could not bring himself to hate No. 1 as he ought to. He had often looked at the colour-print of No. 1 hanging over his bed and tried to hate it. They had, between themselves, given him many names, but in the end it was No. 1 that stuck. The horror which No. 1 emanated, above all consisted in the possibility that he was in the right, and that all those whom he had killed had to admit, even with the bullet in the back of their necks, that he conceivably might be in the right. There was no certainty; only the appeal to that mocking oracle they called History, who gave her sentence only when the jaws of the appealer had long since fallen to dust ...

He had a sudden wild craving for a newspaper. It was so strong that he could smell the printer's ink and hear the crackling and rustling of the pages. Perhaps a revolution had broken out last night, or the head of state had been murdered, or an American had discovered the means to counteract the force of gravity. His arrest could not be in it yet; inside the country, it would be kept secret for a while, but abroad the sensation would soon leak through; they would print ten-year-old photographs dug out of the newspaper archives and publish a lot of nonsense about him and No. 1. He now no longer wanted a newspaper, but with the same greed desired to know what was going on in the brain of No. 1. He saw him sitting at his desk, elbows propped, heavy and gloomy, slowly dictating to a stenographer. Other people walked up and down while dictating, blew smoke-rings or played with a ruler. No. 1 did not move, did not play, did not blow rings. ...Rubashov noticed suddenly that he himself had been walking up and down for the last five minutes; he had risen from the bed without realising it. He was caught again by his old ritual of never walking on the edges of paving stones, and he already knew the pattern by heart. But his thoughts had not left No. 1 for a second, No. 1, who, sitting at his desk and dictating immovably, had gradually turned into his own portrait, into that well-known colour-print, which hung over every bed or sideboard in the country and stared at people with its frozen eyes ...

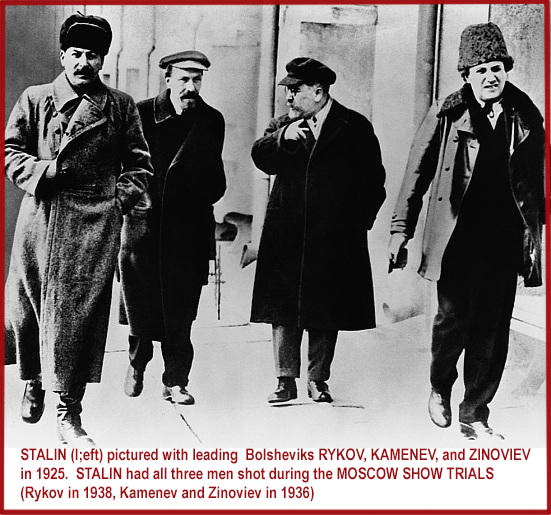

XIX Case Study : STALIN'S SHOW TRIALS, 1936-1938

<https://issuu.com/edcoireland/docs/case-studies-dictatorship-and-democracy-1920.1945/s/15697820.

'...The centrepiece of the Great Terror ... was three show trials of former high-ranking Communists, or Old Bolsheviks ... The Moscow Trials ... were propaganda trials designed to portray the accused men as enemies of the people ... The main aim of the trials was the elimination of all those who had played key roles in the events of 1917, leaving Stalin as the sole link and successor to Lenin ... They were essentially a piece of [deadly] political theatre.'

1917 ... Stalin - Played little role in the October Revolution

1922 ... Stalin - Appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party

1924 ... Death of Lenin - Power struggle between Trotsky and Stalin

1928 ... Stalin - Undisputed leader of the USSR

The First Show Trial : The Trial of the Sixteen

19-24 August 1936

Lev Kamenev, Grigory Zinoviev, and 14 other leading Bolsheviks

Accused of being members of the United Trotskyite-Zinovievite Centre, a [fictitious] terrorist group formed to assassinate the leaders of the CPSU and sabotage the USSR

The Second Show Trial : The Trial of the Seventeen

23-30 January 1937

Yuri Pyatakov, Karl Radek, and 15 other defendants

Charged with being members of the Parallel Anti-Soviet bloc of Trotskyists, assassins & spies

The Third Show Trial : The Trial of the Twenty-One

2-13 March 1938

"Case of the Anti-Soviet Bloc of Rightists and Trotskyites"

Including well-known figures Nikolai Bukharin, Nicolai Krestinsky, Alexei Rykov (former members of Politburo), and Genrikh Yagoda (former head of internal security OGPU/NKVD)

"The work of exterminating Illyich's [Lenin] comrades-in-arms was nearing completion"

i.e. removing those who had opposed Stalin's rise to power or owed their careers to Lenin ―

'...Each trial followed the same format ...The defendants were accused of incredible crimes ... the defendants willingly confessed to crimes of which they could not have possibly been guilty ... the guilty verdicts were decided before the proceedings and were widely publicised within the Soviet Union and abroad ... The defendants were sentenced and shot...'

e.g. 'Before the verdict was announced, Kamenev said, "No matter what my sentence will be, I in advance consider it just".'

DARKNESS AT NOON continued

Rubashov gazed at the damp patches on the walls of his cell. He tore the blanket off the bunk and wrapped it round his shoulders; he quickened his pace and marched to and fro with short, quick steps, making sudden turns at door and window; but shivers continued to run down his back. The buzzing in his ears went on, mixed with vague, soft voices; he could not make out whether they came from the corridor or whether he was suffering from hallucinations...

He shivered. A picture appeared in his mind's eye, a big photograph in a wooden frame: the delegates to the first congress of the Party. They sat at a long wooden table, some with their elbows propped on it, others with their hands on their knees; bearded and earnest, they gazed into the photographers lens. Above each head there was a small circle, enclosing a number corresponding to a name underneath. All were solemn, only the old man who was presiding had a sly and amused look in his slit Tartar eyes. Rubashov sat second to his right, with his prince-nez on his nose. No. 1 sat somewhere at the lower end of the table, four square and heavy. They looked like the meeting of a provincial town council, and were preparing the greatest revolution in human history. They were at that time a handful of men of an entirely new species : militant philosophers. They were as familiar with the prisons in the towns of Europe as commercial travelers with the hotels. They dreamed of power with the object of abolishing power; of ruling over the people to wean them from the habit of being ruled. All their thoughts became deeds and all their dreams were fulfilled. Where were they? Their brains, which had changed the course of the world, had each received a charge of lead. Some in the forehead, some in the back of the neck. Only two or three of them were left over, scattered throughout the world, worn out. And himself; and No. 1...

DARKNESS AT NOON continued

'[Rubashov] had not been in his native country [the home of the Revolution] for some years and found that much was changed. Half the bearded men of the photograph no longer existed. Their names might not be mentioned, their memory only invoked with curses ― except for the old man with the slanting Tartar eyes, the leader of yore, who had died in time. He was revered as God-the-Father, and No. 1 as the Son; but it was whispered everywhere that he had forged the old man's will in order to come into the heritage. Those of the bearded men in the old photograph who were left had become unrecognisable. They were clean-shaven, worn out and disillusioned, full of cynical melancholy. From time to time No. 1 reached out for a new victim from amongst them. Then they all beat their breasts and repented in chorus of their sins.

After a fortnight, when he was still walking on crutches, Rubashov had asked for a new mission abroad. "You seem to be in rather a hurry", said No. 1, looking at him from behind clouds of smoke. After twenty years in the leadership of the Party they were still on formal terms with each other. Above No. 1's head hung the portrait of the Old Man; next to it the photograph with the numbered heads had hung, but it was now gone. The colloquy was short, it had lasted only a few minutes, but on leaving No. 1 had shaken his hand with peculiar emphasis. Rubashov had afterwards cogitated a long time over the meaning of this handshake; and over the look of strangely knowing irony which No. 1 had given him from behind his smoke-clouds. Then Rubashov had hobbled out of the room on his crutches; No. 1 did not accompany him to the door. The next day he had left for Belgium.'

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment