Peveril's Arse

The military mind-set of William the Conqueror was obvious from the start. The first thing he did on landing his army on the south coast of England was to build a castle.

The Chronicle of Battel Abbey reports, "The duke...did not long remain in that place, but went away to a port not far distant called Hastings, and there, having secured an appropriate place, he speedily built a castle of wood."

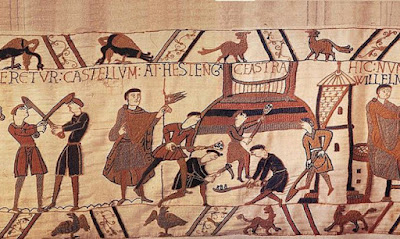

His initial act of castle-building is captured on the Bayeux Tapestry. The Latin inscription reads, "This man has commanded that a fortification should be thrown up at Hastings".

The scene is of a 'motte and bailey' castle in the making. Men with spades pile up a defensive mound of dirt. A wooden structure appears on top.

The motte was an artificial hill, constructed by piling consecutive layers of earth and stones, compacting each one before laying the next. Sides were steep and covered with clay to deter attackers. A timber tower was erected on the flattened area at its summit. A fully operational 'motte and bailey' fort is shown in another scene depicting the earlier capture of Dinan, a stronghold adjoining Normandy.

The advantage of wood and soil forts was their cheapness, using readily available natural materials and employing local unskilled labour. They were also relatively quick to put up.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that William built many more of these basic symbols of dominance as he set about the 'consolidation' of his restless kingdom. In 1067, "It was then told the king, that the people in the north had gathered together and would oppose him there. Upon this he went to Nottingham, and built a castle there, and then advanced to York, where he built two castles: he then did the same at Lincoln and everywhere in those parts."

ANOTHER NORMAN BASTARD

The Old English name for Nottingham was Snotingeham, meaning 'settlement of the people of Snot'. Oblivious to this jest, the inhabitants of Nottinghamshire were about to be delivered up to the ministrations of a Norman overlord called William Peveril.

Several historians have hinted at an interesting provenance for the original castle of Nottingham. An early authority "concluded [it] to be built by William Peveril, or King William the first, his father". A more modern historian writes that, "William the Conqueror, on his way to supress a revolt in York, passed through Nottingham where he ordered his son William Peveril to build a motte and bailey castle". Another source says that the castle "was fortified, with earth and timber, for William the Conqueror during the winter of 1067/8 and was then kept by his henchmen the Peveril family".

There are a couple of points being suggested here. The first is that Peveril was the king's illegitimate son. King William is known to have sometimes signed himself William the Bastard, or Gulielmus Bastardus, recognising his own irregular status. Clearly, he considered being the offspring of unmarried parents was no barrier to promotion.

The second is that Peveril didn't own the castle he built. He held the castle in his capacity as a constable of the king. He was in charge of Nottingham Castle, not Lord Nottingham. Dominating Nottingham town and Sherwood Forest, the castle guarded a key crossing of the River Trent. The main road from London to the north of England was an important transport route for commerce, administration, and the movement of troops.

Built on a high outcrop of sandstone and protected by near-vertical cliffs, the castle provided refuge for an important forward-garrison of King William's soldiers. Overlooking the river crossing, it operated as the gateway to the troublesome rest of England. Peveril's role was to control it for the Crown.

For this service he was amply rewarded, when William I reallocated Anglo-Saxon property to his Norman supporters. This was done soon after his coronation at Westminster in 1066. The Domesday Book of 1086, though compiled twenty years later, gives an idea of the extent of lands granted to William Peveril.

THE HONOUR OF PEVERIL

The 'Honour of Peveril' was scattered over nine counties, with most landholdings contained in Northamptonshire and Nottinghamshire. Multiple ownership of agricultural settlements means that totals like 152 manors or 2,792 households are misleading. A more accurate measure is gained by summing each class of productive assets. As Tenant-in-Chief and/or Lord, Peveril received income from Land and People.

Overall, he owned 496 ploughlands, which were areas of land able to be ploughed by one team of oxen/bullocks in one season. He had 182 lord's plough teams and 425 men's plough teams to work the ploughlands, and rights of access to sufficient meadow and forest land for grazing, fuel and foraging to support his teams.

Peveril also owned 1,507 people who were tied to the land, made up of 779 villagers, 384 small holders, 233 freemen, and 111 slaves. Other manorial responsibilities included 45 flourmills and 3.3 fisheries, 10 churches and 18 priests, 2 burgesses and and 3 men-at-arms.

All of these were legally bound to the manors, mostly part-manors, that belonged to him.

The Domesday Book goes on to assess all the listed property for "annual value", or revenue, accruing to the owners. It provides a current amount for 1086 and a comparative amount from before the Conquest. The lord's return for Peveril was £273/5/7 for 1086 and £245/6/3 under Anglo-Saxon ownership.

Once again, fragmented ownership complicates this picture. Peveril did not necessarily gain all this money each year. As Tenant-in Chief he did not always have 'lordship' of the lands. Some were sub-let to others by the king when the 'spoils of victory' were dispersed. On the other hand, when Peveril did hold both levels of land ownership, he avoided at least one layer of tax or rent to the king.

The widespread nature of his landholdings was probably typical. The amount of cultivated land (496 ploughlands) at each of the separate locations (152 manors) varied from one to fourteen, an average of 3.3. This arrangement was grossly inefficient in economic terms. Most of his land management time would have been spent travelling around to collect his due and checking the serfs weren't withholding some of the harvest.

However, this was the position everyone was in. Land-fractions were part-tradition, part-politics. In theory, preventing one landlord having all his 'domains' in same area was a way of diluting geographical power. Kings, whether Anglo-Saxon or Norman, felt 'safer'.

PECHEFERS

The Domesday Book does not mention the castle at Nottingham as it was the king's. However the following entry of T[empore] R[egis] E[dwardi] landowners is relevant to William Peveril: "In PEAK'S ARSE Arnburn and Hunding held the land of the castle (terra castelli)".

Historian CG Harfield adds, "authorities variously refer to this castle as Peak, Peveril, or its Domesday name Pechefers".

Arnbiorn and Hunding were the pre-Conquest owners of Castleton manor in the Hundred of Blackwell, County of Derbyshire. According to Domesday in 1086, Peveril was Tenant-in Chief and lord of Castleton. It was only 2 ploughlands but its significance was not agricultural.

Peveril, in addition to his stewardship of Nottingham Castle for William I, was Keeper of the Royal Forest of the Peak. He built Pechefers, (Peche[s], Peak's, ers[e], Arse) castle, high above the Hope Valley to administer, ('police'), this vast wilderness which had been specially reserved for the King's use ('hunting'). Nothing unusual in that.

What made Pechefers unique was its dramatic setting, perched on the edge of a 300 foot precipice of weathered rock and scree, and the fact that it was made of stone from the outset. From this imposing site, castellan Peveril governed a region inhabited by deer, wolves, poachers, lead and silver miners, and a few hardy villagers grazing livestock on the moors.

In an age of motte and bailey castles, building in stone was a statement of self-confidence. Remains of Peveril's masonry are found in the curious herring-bone pattern of some curtain-walls. Stone has been laid side by side on the slant, with the next course angled in the opposite direction. Much of Pechefers was remodelled by later Medieval lords, but an English - Heritage site plan makes the original design fairly clear.

The ers[e] part of Pechefers comes from a large limestone cave 280 feet below the castle. Fed by a stream from above, Peak's Cavern, formerly known as the Devil's Arse, emits loud farting noises when in flood.

__________________________________________________________________________

DATA SOURCE:

Open Domesday, Anna Powell and Prof JJN Palmer and University of Hull Team, 2011 <opendomesday.org/name/william-peveril>

CG Harfield, 1991, 'Notes and Documents: A Hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book', English Historical Review, Vol CVI, Iss CCCCXIX, pp 371-392

<https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/CVI.CCCCXIX.371>

Comments

Post a Comment