MA HUAN

Serving as an official translator, Ma Huan travelled on three of Cheng Ho's voyages ― the fourth (1413-1415), sixth (1421-1423), and seventh (1431-1433).

In a 'Notice' or 'Foreword' written in 1416, after his first journey with the Ming fleet, he declared:

"I followed the [mission] wherever it went, over vast expanses of huge waves for I do not know how many millions of li; I saw [these countries] with my own eyes and I walked [through them] in person. So I collected [notes about] the appearance ['ugliness or handsomeness'] of the people in each country, [and] about the variations ['dissimilarity or similarity'] of the local customs, also [about] the differences in the natural products, and about the boundary-limits. I arranged [my notes] in order so as to make a book, which I have entitled The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores [Ying-yai Sheng-lan]."

In fact, it is doubtful that Ma personally visited every one of the twenty countries he describes in the final version of his book (1434). Nevertheless, he certainly had opportunity to interview others on the fleet that did have first-hand experience of those 'foreign' ports he missed out on.

In his 'Foreword of 1416', Ma also acknowledged the influence of an earlier Chinese travel-writer:

"I once looked at [a book called] A Record of the Islands and their Barbarians [or Tao-i chih-lueh by Wang Ta-yuan], which recorded variations of season and of climate, and differences in topography and in peoples. I was surprised and said 'How can there be such dissimilarities in the world?'"

However, after his own experience of 'beyond China', Ma writes "I knew the the statements in [Wang's book] were no fabrications, and that even greater wonders existed".

EXOTIC ANIMALS

Ma Huan had an obvious fascination for unusual animals. This interest goes further than introducing curious oddities for Chinese readers, as any aspiring author might. As he traversed the southern coastline of Arabia, where he first encountered these unfamiliar species, his descriptions become more detailed, and a connection to the Imperial Court emerges.

At Dhufar [Tsu-fa-erh],

"In the mountains they also have the 'camel-fowl'; some of the local people catch them too, [and] come in and sell them. This 'fowl' has a flat body and a long neck; in shape it resembles a crane; the legs are three or four ch'ih [1 metre]; each leg has only two toes; its hair is like a camel's; it eats green peas and other such things; [and] it walks like a camel, hence the name 'camel-fowl'."

Allowing for some inaccuracies, Ma describes the Ostrich. Its relevance is that this flightless bird formed part of the ruler of Dhufar's tribute to the Chinese Emperor:

"On the day when the imperial envoy was returning, the king of this country also sent his chief, who took frankincense, 'camel-fowls', and other such things, and accompanied the treasure-ships in order to present tribute to our court."

At Aden [A-tan] Ma finds the fu-lu and the ch'i-lin:

"The fu-lu resembles a mule; It has a white body and white face; between the eyebrows there starts imperceptibly a pattern of very fine lines which extend over the whole body as far as the four hooves. These fine lines take the form of spaced stripes, [and look] as though the black pattern was painted on."

Joining the zebra was the giraffe:

"The ch'i-lin has two fore-feet which are more than nine ch'ih [3 metres] high; the two hind-feet are about six ch'ih [2 metres] high; the head is carried on a long neck which is one chang six ch'ih [5 metres] long; since the front part is tall and the hind part is low, men cannot ride it; on its head it has two fleshy horns, beside the ears; it has the tail of an ox and the body of a deer; the hoof has three digits; it has a flat mouth; [and] it eats un-husked rice, beans, and flour-cakes."

The intriguing thing about 'zoo-species' like the ostrich, zebra and giraffe was that they were all essentially 'useless'. They had no 'domesticated' or agricultural application ― ""men cannot ride it" ― they could only be admired.

Arab rulers thought of them as ideal presents for someone who already had everything and began including them as part of their tribute to the Emperor. Even Mecca [Mo-ch'ieh], the country of the Heavenly Square [T'ien fang, the Ka'ba or 'cube-house], saw fit to send "ch'i-lin, lions, 'camel-fowls', and other such things back to the Chinese capital in the treasure-ships."

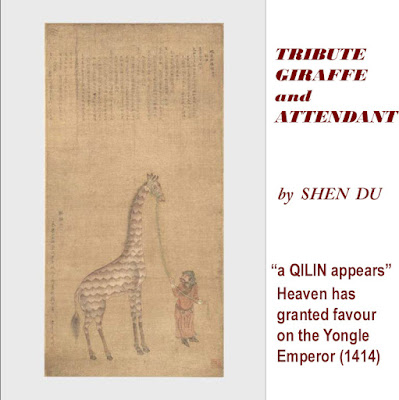

The diplomatic 'fashion' for consigning strange animals to China began with a gift from Bengal in north-eastern India. A giraffe was presented to the Ming Court by the Bengal ruler in 1414. The South Asian seems to have received it as a gift from East Africa in the previous year. The arrival of the giraffe caused a sensation in the Chinese capital. The Yongle emperor ordered an artist named Shen Du to draw the animal.

Now famous and much copied, 'The Tribute Giraffe and Attendant' was annotated with Chinese characters that 'explained' its subject.

"When a sage possesses the utmost benevolence so that he illuminates the darkest places, a qilin appears. This shows that Your Majesty's virtue equals that of Heaven; and its merciful blessings have spread far and wide and from its harmonious vapours there has emanated a quilin which will be an endless bliss to the state for myriad years."

A qilin is a mythical creature supposed to only appear in times of great peace and tranquillity. It was one of the four sacred animals of China, along with the dragon, phoenix and tortoise. The appearance of a giraffe in Nanking was interpreted as this auspicious sign, 'evidence' of the favour Heaven had granted on the Yongle emperor's reign.

A tall, swaying ch'ih-lin in the palace gardens was the right superstitious tonic for a ruler who had usurped the throne from his nephew. Anything that might be interpreted as Heavenly approval was happily received, and this encouraged other rulers in the Western Ocean to try and repeat the trick.

CLIENT KINGDOM

Another characteristic of Ma Huan's writing is his reference to the fleet's history. Each voyage had a political impact and that message was reinforced by subsequent visits.

Ma was well aware of the imperial intention behind the mighty armadas. It was to impress on local regimes the absolute dominance of the Central Country over the Maritime Silk Road and associated trade networks. If it was deemed necessary to mount a 'police' action on individual

sailing routes or points of exchange, the eunuch admiral Cheng Ho had the military resources to carry it out.

A critical part of the system for navigators was the 'intersection' between the Southern Ocean (China's 'backyard'), and the rich market-places of India and Arabia. This junction occurred at the Malacca Strait, a natural 'chokepoint' between the large island of Sumatra and the Malayan peninsular.

On the Sumatran side, Cheng Ho's troops intervened against a pirate-king threatening San-fo-ch'i (south Sumatra) and a rebel-king threatening Su-men-ta-la (north Sumatra) to restore stability. However the Malayan side remained 'unsettled'. Ma Huan writes in detail about the 'resolution' of this uncertainty.

"Formerly this place was not designated a 'country'...There was no king of the country; it was controlled only by a chief. This territory was subordinate to the jurisdiction of Hsien Lo [Siam, Thailand]; it paid an annual tribute of forty liang of gold; [and] if it were not [to pay] then Hsien Lo would send men to attack it...

"In the seventh year of the Yung-lo [period], [the cyclic year] chi-ch'ou [1409], the Emperor ordered the principal envoy the grand eunuch Cheng Ho and others to assume command [of the treasure-ships] and to take the imperial edicts and to bestow upon this chief two silver seals, a hat, a girdle and a robe. [Cheng Ho] set up a stone tablet and raised the place to a city; [and] it was subsequently called the 'country of Man-la-chia' [Malacca]. Thereafter Hsien Lo did not dare invade it...

When Hsien Lo began to forget this 'sovereign' act by the dominant power in the region, its ruler was promptly, and effectively, rebuked. In 1431 a representative from Malacca complained that the kingdom of Siam was once again obstructing tribute missions to the Ming Court. The Xuande emperor dispatched Cheng Ho to Thailand with a chilling message: "You, king, should respect my orders, develop good relations with your neighbours, examine and instruct your subordinates, and not act recklessly or aggressively."

It can be seen from these actions in the vicinity of the Strait that establishing 'regional security' was a Chinese imperative. They sought a series of stable political platforms from which to base orderly, that is to say 'controlled, marketing.

By the time of Ma's last visit to Malacca, progress had been made towards this goal:

"There is one large river whose waters flow down past the front of the king's residence to enter the sea; over the river the king has constructed a wooden bridge, on which are built more than twenty bridge-pavilions, [and] all the trading in every article takes place on this [bridge]."

The bridge of trading booths may have been an indigenous initiative. Not so the development of a 'government depot' by Cheng Ho.

"Whenever the treasure-ships of the Central Country arrived there, they at once erected a line of stockading, like a city wall, and set up towers for the watch-drums at four-gates; at night they had patrols of police carrying bells; inside, again they erected a second stockade, like a small city-wall, [within which] they constructed warehouses and granaries; [and] all the money and provisions were stored in them. The ships which had gone to various countries returned to this place and assembled; they marshalled the foreign goods and loaded them in the ships; [then] waited till the south wind was perfectly favourable."

Military strength, armed Chinese soldiers, underpinned this 'safe harbour'. The nautical charts for the fleet, preserved in Wu-pei-chih or Mao Kun's Map, marks the site of Malacca city on one side of the river and the guan chang ['government depot'] on the other. This left no doubt in any navigator's mind about who was in charge here.

PRICE FIXING

The two big market-places for pepper in the medieval world were the island of Java and the Malabar Coast in Southwest India. The Malabar ports were therefore an important destination for Cheng Ho's fleet on all seven of its voyages.

Ma Huan writes of Quilon (Ko-lin), Cochin (Ko-chih), and Calicut (Ku-li) as the main ports of a hinterland that "has no other product, but [produces] only pepper". Calicut in particular is called "the great country of the Western Ocean".

Accordingly:

"In the fifth year of the Yung-lo period [1407] the court ordered the principal envoy the grand eunuch Cheng Ho and others to deliver an imperial mandate to the king of this country and to bestow on him a patent conferring a title of honour, and the grant of a silver seal, [also] to promote all the chiefs and award them hats and girdles of various grades.

"[So Cheng Ho] went there in command of a large fleet of treasure-ships, and he erected a tablet with a pavilion over it and set up a stone which said 'Though the journey from this country to the Central Country is more than a hundred thousand li, yet the people are very similar, happy and prosperous, with identical customs. We have here engraved a stone, a perpetual declaration for ten thousand ages'."

Orderly marketing, like political stability, was a policy imperative for the Imperial Court, but in a place so distant from the Central Country, a form of 'soft power' was employed to gain that end. Flowery language promising 'eternal friendship' and lots of presents for the local elite was thought more appropriate than a naked display of force. The treasure-ships were more significant here for the contents of their holds, not their cannon.

The great attraction of Calicut was price fixing:

"The king has two great chiefs who administer the affairs of the country; both are Muslim [as was Cheng Ho (and Ma Huan)]...Their two great chiefs receive promotion and awards from the court of the Central Country.

"If a treasure-ship goes there, it is left entirely to the two men to superintend the buying and selling; the king sends a chief and a Che-ti Wei-nochi [leader of Hindu trading caste] to examine the account books in the official bureau; [and] a high officer commanding the ships discusses the choice of a certain date for fixing prices. When the day arrives, they first of all take the silk embroideries and the open-work silks, and other such goods which have been brought there, and discuss the price of them one by one; [and] when [the price] has been fixed, they write out an agreement stating the amount of the price; [this agreement] is retained by these persons.

"The chief and the Che-ti, with his excellency the eunuch, all join hands together, and the broker then says 'In such and such a moon on such and such a day, we have all joined hands together and sealed our agreement with a hand-clasp; whether [the price] be dear or cheap, we will never repudiate or change it'.

"Once the money-price has been fixed after examination and discussion...there is not the slightest deviation."

This system pleased the Chinese, who held the advantage throughout. It ultimately pleased the king of Calicut, "who sends a chief and a writer and others to watch the sales: thereupon they collect the duty and pay it into the authorities". It may have even pleased the merchants and it was almost certainly an enriching process for the chiefs who administered it. The only party who did not have a say were the growers.

Ma Huan writes:

"As to the pepper: the inhabitants of the mountainous countryside have established gardens, and it is extensively cultivated. When the period of the tenth moon arrives, the pepper ripens; [and] it is collected, dried in the sun, and sold. Of course, big pepper-collectors come and collect it, and take it up to the official storehouse to be stored; if there is a buyer, an official gives permission for the sale."

The Chinese interest was not concerned with the plight of the people. They were satisfied with the principles of political stability, as in Malacca, and/or economic order, as in Calicut. Whether the subservient regime, or market, produced just outcomes for the inhabitants was irrelevant. Their notion of international influence and exchange was essentially 'state to state', a Confucian standard that assumed 'no social change' as a philosophical ideal. Pretty much any system would have served, as long as it was 'fixed' and did not challenge an existing 'order'.

__________________________________________________________________________

MAIN SOURCES:

JVG Mills, 1970, MA HUAN Ying-yai Sheng-lan 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores',

Cambridge University Press; Hakluyt Society. <archive.org/items/ying-yai-sheng-lan-1433>

Tansen Sen, 2016, 'The impact of Zheng He's expeditions on Indian Ocean interactions', Bulletin of SOAS, 79.3, 609-636.

Comments

Post a Comment