CHAU JU-KUA

Chau Ju-kua was Inspector of Foreign Trade at the Chinese port of Ts'uan-chou. In about

1226 he wrote a book called Chu-fan-chih, which translates to 'Description of Barbarous Peoples' or 'Records of Foreign Nations'.

The contents of his book are neatly summarised in a contemporary catalogue entry:

"Chu-fan-chih, the Inspector of Foreign Trade, Chau Ju-kua, records (in this book) the several foreign countries and the merchandize which come from them".

(Ch'en Chen-sun, 'Descriptive Catalogue' of family library, ca. 1234-1237)

It is evident from this short review that Chau had two advantages for producing a useful text. Because of his official role at the port, he had access to reliable data on the type of goods imported. In addition he had the opportunity for face to face communication with foreign merchants and ship-captains to supplement these basic facts.

A further point in the author's favour was the existence of a literary foundation on which to build. Fifty years before, around 1178, Chou K'u-fei wrote Ling-wai-tai-ta, which translates as 'Regions Beyond Mountain Passes'. Other attempts to render the meaning of Chou's title have been made, including 'Representative Answers from the Region beyond the Mountains' and 'Notes Answering [Curious Questions] from the land beyond the Pass'. They suggest that the scope of his book was not confined to the same economic focus as Chu-fan-chih.

However, such was Chou's understanding of the South China Sea and Indian Ocean trade that Chau often quoted, and misquoted, this earlier work. Extracts from Ling-wai-tai-ta still provide a precise introduction to 'Records of Foreign Trade'.

"The coast departments and the prefectures of the empire now stretch from the north-east to the south-west as far as K'in-chou [Tongking or Kiau-chou frontier], and these coast departments and prefectures (are visited by) trading ships. In its watchful kindness to the foreign Barbarians our Government has established at Ts'uan-chou and at Kuang-chou [Zaitun and Canton] Special Inspectorates of Shipping, and whenever any of the foreign traders have difficulties or wish to lay a complaint they must go to the Special Inspectorate.

"Every year in the 10th moon the Special Inspectorate establishes a large fair for the foreign traders and (when it is over) sends them (home). When they first arrive (in China) after the summer solstice, (then it is that) the Inspectorate levies (duties) on their trade and gives them protection.

"Of all the wealthy foreign lands which have great store of precious and varied goods, none surpass the realm of the Arabs (Ta-shi). Next to them comes Java (Sho-p'o); the third is Palembang (San-fo-ts'i)."

(Chou K'u-fei, Ling-wai-tai-ta, 1178 AD)

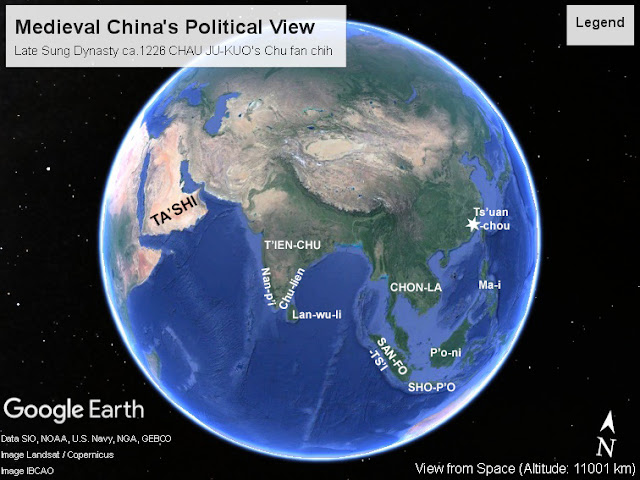

In Part 1 of Chu-fan chih, Chau itemises 45 'Countries' plus 8 'Countries in the Sea' (islands). In Part 2 he describes 43 commodities imported from these sources into China. This creates a sort of narrative-map showing how much officials knew about the world outside the Empire.

To simplify Chau's detailed lists, there were five main economic zones on the maritime Silk Road. These were places where goods were gathered in from the surrounding regions for shipping on to China. Far to the west was Ta-shi, the land of the Arabs, and more specifically the ports along the southern coasts of Arabia and Persia.

Moving east were the ports of southern India on the coastlines of Malabar (SW) and Maabar (SE). And closest to home was the north-eastern shores of Sumatra, called San-fo-ts'i, the island of Java, known as Sho-p'o, and the mainland of South-East Asia, or Chon-la.

THE ARABS : TA-SHI

"The Ta-shi are to the west and north of [Chinese port-city] Ts'uan-chou at a very great distance from it, so that the foreign ships find it difficult to make the voyage direct. After these ships have left Ts'uan-chou they come in some forty days to Lan-li [NW Sumatra], where they trade. The following year they go to sea again, when with the aid of the regular wind [the monsoon] they take some sixty days to make the journey on to Ta-shi].

"The products of the country are for the most part brought to San-fo-ts'i [NE Sumatra], where they are sold to merchants who forward them to China." ['This country (San-fo-ts'i), lying in the ocean and controlling the straits (literally "gullet") through which the foreigner's sea and land traffic (literally "ship and cart") in either direction must pass...If a merchant ship passes by without entering, their boats go forth to make a combined attack, and all are ready to die (in the attempt). This is the reason why this country (San-fo-ts'i) is a great shipping centre.' Chou Ku'fei adds, 'It is the most important port-of-call on the sea-routes of the foreigners, from the countries of Sho-p'o (Java) on the east and from the countries of the Ta'shi (Arabs) and Ku-lin (SW India) on the west, they all pass through it on their way to China.']

"The capital of the country (of the Ta-shi), called Mi-su-li, is an important centre for the trade of foreign peoples [Hebrew Mizraim, Arabic Misr, Cairo, capital of Egypt]...

The king, the officials and the people all serve (or revere) Heaven. They also have a Buddha by the name of Ma-hai-wu [In Cantonese, Ma-ha-mat, the Prophet Mohammed]...

At the New Year for a whole month they fast and chant prayers [the Fast of Ramadan]. Daily they pray to Heaven five times."

"This country (or people) was originally a branch of the Persians. In the ta-ye period of the Sui dynasty (AD 605-617) there lived a high-minded and wise man among the Persians who found deep down in a hole a stone bearing an inscription, and this he took for a good omen. So he called the people together, took by force the things necessary (for arming men) and enrolled followers, who gradually increased in number till he became powerful enough to make himself king, and then he took possession of the western portion of Po-ssi (Persia)... Before (that)...they were call 'White-robed Ta-shi'; after...they were called 'Black-robed Ta-shi'.

"A foreign trader by the name of Shi-na-wei, a Ta-shi by birth, established himself in the southern suburb of Tsuan-chou. Disdaining wealth, but charitable and filled with the spirit of his western home, he built a charnel house in the south-western corner of the suburb (or outside the city in the south-west direction) as a last resting place for the abandoned bodies of foreign traders. The Customs Inspector Lin Chi-k'i has recorded this fact. [translator's note: 'On the Ling-shan, or "Hill of Souls", in the south-eastern part of Ts'uan-chou were the Mahommedan tombs, or "the tombs of the Medina-men". Lin Chi-k'u, Customs Inspector of Min (Fu-kien) died in 1176'.]"

This and other paragraphs indicate that trade between Arab voyagers and Chinese ports had been going on for many centuries. Contact was so continuous that a large community of Moslems had become established in Ts'uan-chou. The long tradition of trade was in large part the result of rare goods like large elephant tusks and "dragons blood" not being available from sources in South East Asia. The inventory of Ta-shi commodities was unique.

JAVA : SHO-P'O

Java and its dependencies are given a more complete report by Chau Ju-kua that included imports as well as exports. China was receiving a lot of foreign produce but this had to be paid for somehow. Essentially, the Javanese exchanged what the Chinese wanted for what they wanted. This did not always fit neatly into the larger country's desires, at least at a government level.

Chau writes, "There is a vast store of pepper in this foreign country and the merchant ships, in view of the profit they derive from that trade, are in the habit of smuggling (out of China) copper cash for bartering purposes. Our Court has repeatedly forbidden all trade (with this country), but the foreign traders, for the purpose of deceiving (the government), changed its name and referred to it as Su-ki-tan [ie Central Java]."

The translator notes, "Chinese copper cash appears to have been in great demand in the Archipelago...[The Annals of the Sung Dynasty, Sung-shi] says that...'the traffic of merchant ships between China and foreign countries had the effect of scattering abroad the copper cash for the use of our country'. For this reason the exportation of cash to any place beyond the straits near Hang-chou was prohibited...In the 9th year kia-ting (1216) the High Commissioners for the inspection of government affairs began their Report as follows: 'Since the appointment of Inspectors of Foreign trade, the issue of copper cash to ships engaged in foreign trade at the open ports has been forbidden. At the end of the shan-hing period (about 1163) the Ministers drew attention to the irregularities arising from the Inspectors of Foreign trade at Ts'uan-chou and Canton, as well as the two Mint Inspectors of the south-western Provinces, allowing vessels to clear with return cargoes containing gold and copper cash'."

The translator concludes, that despite "the repeated complete prohibition of the exportation of cash", it was evident that "during certain periods it was not strictly enforced". The Edicts restricting activities "by Ocean going ships" were partial and contradictory ― "since traffic with Sho-p'o (Java) was specifically prohibited...the restriction could be easily evaded by clearing ships for another country ― as Chau Ju-kua tells us traders did."

Chau is alert to the the flimsiness of this fraud. As he explains, "Su-ki-tan is a branch of the Sho-p'o country...The people use as a medium of trade pieces of alloyed silver cut into bits like dice and bearing the seal of the Fau-kuan ['Foreign official'] stamped on it...For all their other trading they use (this money) which is called 'Sho-p'o kin' ('Java money'), from which it may be seen that this country is (identical with) Sho-p'o."

On a happier note for China's 'balance of trade', in Su-ki-tan too there "is a great abundance of pepper...The pepper-gatherers suffer greatly from the acrid fumes they have to inhale, and are commonly afflicted with headache (malaria) which yields to doses of (ssi)-chuan-kung. As cinnabar is much used in cosmetics by the Barbarian women and also for dyeing the fingernails and silk clothing of women, foreign traders look upon these two articles as staples of trade." Here was an example of how foreign exchange was supposed to work, according to Chinese bureaucrats.

_________________________________________________________________________

F Hirth & W Brockhill (transl.), 1911, Chau Ju-kua: His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and the Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-fan-chi

<archive.org/details/ 31924023289345>

Comments

Post a Comment