Cultural Regionalism

SOME CULTURAL PRACTICES START, SOME STOP, SOME CHANGE, AND SOME DO NOT

BONES HAVE A CLEAR AND DIRECT LINK WITH THE PAST: THEY REMEMBER IT

Previous posts have described the first archaeological traces of Aboriginal settlement along the coast of southwest Victoria and southeast South Australia.

Sites at Cape Duquesne cliffs, Bridgewater South and Koongine caves, and Wyrie Swamp, have occupation remains dating from 13,000 to 9,000 years ago. They reveal an economic picture of subsistence existence during terminal Pleistocene ― Holocene transition, explaining diet and and the development of a "complete tool-kit" for practical survival.

However, there is little among these artefacts that evokes their communal lives. Hunters and gatherers lived together, communicated with each other, had children and grieved the loss of family members. The difficulty is that only tangible elements are preserved long enough for archaeologists to dig them up millennia later.

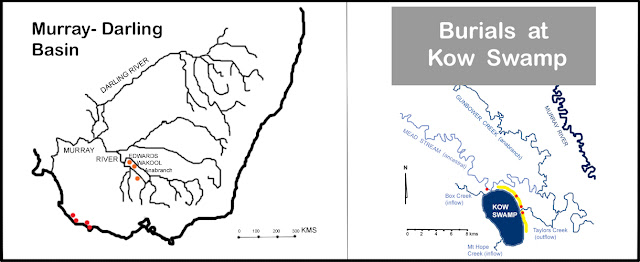

One way to gain access to "lives lived" is to investigate human burials. An area rich in excavated cadavers is the Murray River Valley. Some of these graves date to the same time as our early coast-dwellers. The purpose of this post is not to seek possible similarities though. Instead it is about uniqueness.

A claim is often made that prehistoric Australians shared a continuous aesthetic from their arrival on the continent ― "the oldest culture on earth". A good example of this not being the case is provided by the Kow Swamp - Coobool Creek people

At Kow Swamp 40 individuals were exhumed. They were buried in banks of Cohuna Silt on the eastern shore of the paleo-lake near its outflow stream Taylors Creek. The graves were shallowly dug in soft soils but the skeletal material had been preserved by carbonate mineralisation. Their bodies had been interred with some care although not necessarily according to one ceremonial pattern.

"Orientation of cadavers included full extension, crouching and tight flexion. Stone artefacts, ochre, shells and marsupial teeth were placed in some graves. At least one individual had been cremated".

Radiocarbon dating of bone collagen from KS1, KS9 and KS14 returned ages of 11,800 +/-800, 10,600 +/-700 and 9,700 +/-600 years before present (YBP). Results from freshwater mussel shell associated with KS5, KS14 and KS17 were 15,300 +/-1100, 12,900 +/-300 and 13,400 +/-500 YBP. Charcoal fragments around KS9 produced 4 dates ranging from 10,900 +/-700 to 6,900 +/-900. A conservative estimate of core dates suggests a 4,000 year period, from about 13,000 to 9,000 YBP,

Kow Swamp is hardly a conventional cemetery in the modern sense. If these dates are reliable then we are are looking at just 40 people who died over a very long timespan. What makes the site distinctive is that some of the skulls, including the Cohuna-cranium, KS5 and KS37, show definite signs of "cranial deformation". They have been intentionally "head-shaped", with flattened foreheads and elongated occipits (back of the skull).

At Coobool Creek remains of more than 100 individuals were roughly excavated in 1950. The bones lack records of precise location and stratigraphy. Because they were put in gelatin to prevent further decay, dating is limited to one Uranium/Thorium age of 12,500 +/-400 YBP on bone from CC65.

33 crania from this collection were able to be reconstructed. Their "archaic characteristics" placed them with the Kow Swamp group, rather than Late Holocene or 'modern' Aborigines retrieved elsewhere along the Murray Corridor. In addition, CC1, CC49 and CC65 showed "clear evidence for culturally manipulated changes in cranial shape".

The same rough excavation techniques were visited on an unknown number of skeletons near Nacurrie Siding (Merran Creek), of which only one was reconstructed. The "Murrabit skull", or Nacurrie 1, was described as "almost an identical twin to Cohuna". An AMS collagen date from postcranial bone fragments was obtained of 11,440 +/-160 YBP. The relevance of this population, intermediate between Kow Swamp and Coobool Creek, was that N1 displayed the same "distorted head shape".

The collections from these three sites were returned to local descendant groups for reburial. Before repatriation, some of the Coobool Creek crania were able to be systematically measured and compared. This scientific investigation has prompted a reinterpretation and extension of the original thesis.

31 individuals were examined. 19 were ruled "Not Deformed". However 4 (CC1, CC41, CC65, CC66) were classified as "altered by artificial deformation" and a further 8 (CC7, CC9, CC12, CC29, CC35, CC47, CC49, CC82) showed "more subtle signs of deformation". This implies that significant proportions of the three populations may have engaged in this cultural practice.

"Currently [2010], evidence of intentional deformation is restricted to three terminal Pleistocene - early Holocene sites, Coobool Creek, Nacurrie and Kow Swamp, separated on a transect running south-east to north-west by approximately 100 km, and all close to the Murray River".

Comparisons with head-binding practices in other ethnic populations indicate that the early Australian method was "repetitive hand manipulation by the neonate's mother", rather than tight bandaging or "boarding". The general principle behind head shaping is that "growth is inhibited in one direction and promoted in another".

A new born child's skull is naturally flexible to ease its passage through the birth canal. If repeated pressure is applied to parts of "the vault" in the first year, until the "fontanelles fuse" and the bone thickens, an infant's head can be safely re-shaped into a form that is then maintained through life. The final result may be down to the experience and diligence of the nursing mother, or community attitudes on the most desirable adult profile. Either way, the change is permanent.

The Kow/Nacurrie/Coobool connection is an interesting one. The altered crania were a distinctive cultural expression of group identity. We do not know why head shape was modified, or why it started and then stopped. The crania from this region are testimony that at some stage the fashion was adopted by particular groups, and not others, and that it was not continued as an inherited custom by later populations.

The lesson from this unusual tradition is that culture, including Aboriginal culture, is not automatically transferrable in time or space. It is in many instances, specific to geographical place and historical occurrence.

In the absence of real evidence of the culture of the early coastal people occupying SW Victoria and SE South Australia, it would be wrong to apply the behaviour of others to them as if it was their own. There may be genetic similarities or environmental coincidences but the assumption of direct cultural affinity is a step too far.

__________________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES:

AG Thorne & PG Macumber, 1972, 'Discoveries of Late Pleistocene Man at Kow Swamp', Nature, 238, 316-319

T Stone & ML Cupper, 2003, 'Last Glacial Maximum ages for robust humans at Kow Swamp, southern Australia', Journal of Human Evolution, 45, 99-111

P Brown, 1981, 'Artificial Cranial Deformation: a component in the variation in Pleistocene Australian Aboriginal crania', Archaeology in Oceania, 16, 156-167

P Brown, 1987, 'Pleistocene homogeneity and Holocene size reduction: the Australian human skeletal evidence', Archaeology in Oceania, 22, 41-67

AC Durband, 2008, 'Artificial cranial deformation in Pleistocene Australians: the Coobool Creek sample', Journal of Human Evolution, 54, 795-813

P Brown, 2010, 'Nacurrie 1: Mark of ancient Java, or a caring mother's hands, in terminal Pleistocene Australia?',

Journal of Human Evolution, xxx, 1-20

C Pardoe, 1988, The cemetery as symbol: The distribution of prehistoric Aboriginal burial grounds in southern Australia', Archaeology in Oceania, 23.1, 1-16

C Pardoe, 1993, 'The Pleistocene is still with us: Analytical constraints and possibilities for the study of ancient human remains in Archaeology', in Smith, Spriggs, Frankhauser (eds), Sahul in Review: Pleistocene Sites in Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia, (ANU Occasional Papers in Prehistory No 24)

C Pardoe, 1995, 'Riverine, biological and cultural evolution in southeastern Australia', Antiquity, 69, 696-713

J Littleton & H Allen, 2007, 'Hunter-gatherer burials and the creation of persistent places in southeastern Australia', Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 26, 283-298

Comments

Post a Comment